Rainbow Kitchen Community Services

October 27, 2014

The Monongahela Incline

November 24, 2014 Pittsburgh is home to three rivers and two in cable car inclines. Most residents will tell you that the Monongahela River and the Allegheny River join at the point to create the Ohio River. Some can tell you which incline is the Duquesne, and which is the Mon. However, many don’t know the intricate details that make our rivers and cable car system so noteworthy.

Pittsburgh is home to three rivers and two in cable car inclines. Most residents will tell you that the Monongahela River and the Allegheny River join at the point to create the Ohio River. Some can tell you which incline is the Duquesne, and which is the Mon. However, many don’t know the intricate details that make our rivers and cable car system so noteworthy.

Sure, you can capture some stunning views down by the water or up in the incline, but that is not the only reason these pieces of Pittsburgh infrastructure are populated. Rather, much of the acclaim comes from commercial use.

Pittsburgh’s Rivers

The Allegheny River is 325 miles long. However, only about 75 miles are navigable. This river is primarily used for recreation but does sees some commercial traffic. The Allegheny starts in the middle of Pennsylvania and joins the Monongahela to form the Ohio River in Downtown Pittsburgh. At 130 miles long, the Monongahela River originates in Marion County, WV and flows north into Pennsylvania counties. There have been three U.S. Navy ships named after this river.

The Allegheny River is 325 miles long. However, only about 75 miles are navigable. This river is primarily used for recreation but does sees some commercial traffic. The Allegheny starts in the middle of Pennsylvania and joins the Monongahela to form the Ohio River in Downtown Pittsburgh. At 130 miles long, the Monongahela River originates in Marion County, WV and flows north into Pennsylvania counties. There have been three U.S. Navy ships named after this river.

The Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers join at The Point where the Ohio River flows to the Ohio/West Virginia border. At 981 miles long, it is the 10th longest river in the United States. The Ohio River is the main source of drinking water for more than three million people, across 15 states. It is estimated that nearly 10% of the U.S. population lives within the Ohio River Basin.

Water navigation is a prime use for cargo shipping. The Port of Pittsburgh is the second busiest inland port in the country. In 2014 it was in the top 20 busiest ports of any kind in the U.S. Nearly 41 million tons of cargo is shipped and received each year in the Pittsburgh Port.

Barge shipping typically boasts a low shipping cost that averages around 0.97 cents per ton mile. In comparison, shipping by rail more than doubles the cost, which is then doubled again for shipping by truck. The primary cargo in the Port of Pittsburgh is coal. However, millions of tons of other raw products, manufactured goods, petroleum products, and various chemicals are shipped by barge.

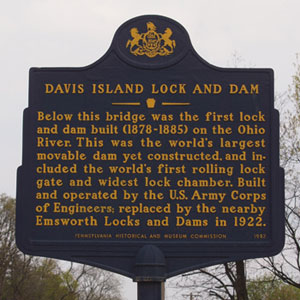

It is through a system of locks and dams that make inland waterway navigation possible. Pittsburgh holds the key to the waterways of the United States by operating 17 sets of locks and dams along its three rivers.

Pittsburgh’s Lock and Dam System

The locks and dams system is necessary for year-round transportation. It maintains a constant channel in which the river depth is maintained at nine feet. The natural riverbed changes throughout the year and can be uneven or shallow at points due to rainfall and dry periods. The dams create an ‘aquatic staircase’ to prevent this from happening. Each step on the slope of the riverbed is a pool of water. The normal flow of the river runs through these pools and the excess flows over the dam into the next pool and on down the river.

Each dam on a navigable river has at least one lock chamber to enable river traffic to go safely from one pool level to the next. The lock chamber is essentially a concrete box with two matching gates at each end that can open or close only when the water level is the same on both sides. The Allegheny River utilizes only single chamber locks as they see only an average of four million tons of activity per year. In comparison, the four double chamber and two single chamber locks on the Monongahela River see about 54 million tons. All three locks on the Ohio River are double chamber.

The Port of Pittsburgh Commission maintains both fixed crest dams and gated dams. With fixed crest dams, the operator is able to make minor adjustments to the rate of flow. All eight of the dams on the Allegheny River are fixed crests. This means the water flows freely over the concrete box described above. The Monongahela has two fixed and four gated dams. The Ohio River has one fixed and two gated.

This system of water navigation has made transportation along the water a vital part of Pittsburgh’s economy.

Pittsburgh’s Inclines

While Pittsburgh’s location at the juncture of three rivers makes water transportation easy, land transportation in the region has always been difficult. The terrain is defined by hills that made it difficult for engineers in the late 19th century to create transportation systems. People and industries needed a way for the hilltop communities to commute to the downtown area near the river. The solution became inclined plane railways.

The Monongahela Incline, built in 1870, was the first of Pittsburgh’s inclines. This came a full three years before San Francisco’s first successful cable car line went into operation. “The Mon” is still located near the south end of the Smithfield Street Bridge on Carson Street, today. The popularity and success of the Mon led to an incline boom. Within a year one popped up in Mount Oliver, then the Duquesne Incline in 1877. By 1901 there were 13 more.

One incline could transport several thousand people on any given day. For over 30 years Pittsburgh’s inclines were the marvel of the nation. However, the Twentieth Century brought with it increased engineering might, the rise of the automobile, and air travel.

Even competition provided by the electric street car began to erode the ridership of Pittsburgh’s inclines. Even more competition came when roadways improved and tunnels were created, making it easier to travel through the city. In time, inclines were no longer the main form of commuting for Pittsburghers. Today, only two inclines remain: the Mon and the Duquesne Incline.

The Duquesne & Monongahela Inclines

These inclines act more as a tourist attraction than a form of transportation. It is like taking a step back in time as you ride on the nostalgic cable cars atop the hills of Pittsburgh. Both inclines offer observation platforms for visitors to view and photograph the downtown area known as the ‘Golden Triangle.’

Today Pittsburgh’s Monongahela Incline is the oldest and the steepest incline in the United States. It is 635ft long and 367ft high with an angle of 35 degrees. The incline was purchased in 1964 by the Port Authority of Allegheny County. One reason for its success is its ideal location in the heart of Station Square.

The Duquesne Incline has a length of 793ft, a height of 400ft and a grade of 30 degrees. It travels six miles per hour and can carry 23 passengers per car at a time. It is located near the Fort Pitt Bridge at 1220 Grandview Avenue. In 1962 the Duquesne incline was closed for repairs. Due to the extent of the damage, it was feared the incline would not reopen. However, the local community joined together and raised enough funds to reopen the incline in 1963. One year later it was purchased by the Port Authority who leases it for $1 to the Society for the Preservation of the Duquesne Incline.

The Duquesne incline is different from the Mon Incline. It is a nostalgic view that offers original Victorian cars with ornate wooden panels, brass fittings, and amber glass windows. The Duquesne Incline’s upper station houses a museum of Pittsburgh history and a storehouse of information on inclines around the world.