Autism Awareness Month: Autism Resources, Events, and More

April 3, 2025

Positively Pittsburgh: The Podcast

April 24, 2025

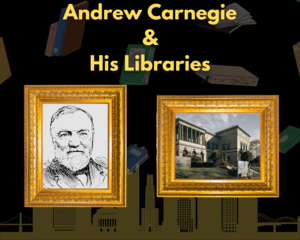

It’s National Library Week and we thought it would be fun to explore the history of the Carnegie Libraries and Andrew Carnegie himself.

Who was Andrew Carnegie?

Andrew Carnegie, one of the richest men of the Gilded Age, is often remembered for his immense philanthropy, with the libraries he funded being at the top. Between 1883 and 1929, Carnegie funded the construction of over 2,500 libraries, with around 1,700 in the United States alone. His goal was to provide people, particularly the working class, with free access to books and knowledge. He believed that education and self-improvement were the keys to personal and societal progress. But while his library legacy is impressive, Carnegie’s life and business practices reveal a darker side of the man who gifted the world with books.

A New Life

Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, to a working-class family. His father was a handloom weaver when the power loom arrived, he was put out of work. In 1848, Carnegie and his family emigrated to the United States. When he was just 12 years old, Carnegie began working in a cotton factory as the bobbin boy, and when he was 14, he started working for the Pennsylvania Railroad as a messenger in their telegraph office. It was while working here that he invested his money while climbing the ladder of the railroad, and by age 30 he had amassed quite a bit of wealth. He eventually left the railroad to work for the Keystone Bridge Company. But he was destined for more.

In the 1870s, he founded a steelworks company that eventually became the Carnegie Steel Company in the Pittsburgh, PA area. The steel works would go on to make him one of the wealthiest men in history. He took American manufacturing to new heights with vertical integration and borrowing steel making processes from Great Britain. Carnegie also hired Henry Clay Frick to work at the steel mill. He sold the company to J.P. Morgan in 1901 for $480 million (equivalent to billions today), where it became part of U.S. Steel. After the sale, he turned his attention to philanthropy.

The Gospel of Wealth

Carnegie believed that the wealthy had a moral obligation to use their wealth to help the public, this became what he called the Gospel of Wealth. The Gospel of Wealth stated that the rich should use their surplus of money for the “improvement of mankind.” In fact, he said, “A man who dies rich dies disgraced.” He viewed libraries as engines of opportunity. In his mind, anyone willing to work hard and educate themselves could rise above their circumstances, just as he had. By funding libraries, he gave communities the tools for self-education, job training, and upward mobility.

A Dark Legacy

Carnegie’s generosity cannot be separated from the way he made his fortune. His steel empire was built on the backs of workers who endured long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions. Perhaps the most infamous event tied to his business was the Homestead Strike of 1892, a violent labor conflict at the Homestead Steel Works in Homestead, PA. Union works chose to strike because the steel company wanted to lower the bottom of the sliding scale pay by 15%. Carnegie was away in Scotland at the time, but his right-hand man, Henry Clay Frick, took a hardline stance against the striking workers. Frick had extreme disdain for unions of any kind. Frick refused to negotiate any furtherIn what would become a grave mistake, Frick hired Pinkerton agents to break the strike.

On July 6, 1892, approximately 300 Pinkertons descended upon Homestead via barge. The resulting clash lasted hours and left several people dead and many injured. The Pinkertons left on trains and were not arrested for the murders of any of the Homestead workers or citizens. The Pennsylvania National Guard was sent in, and the area was placed under martial law. Although Carnegie later expressed regret, he had approved of Frick’s actions.

On the Backs of Many

Critics argue that Carnegie used his philanthropy to polish his public image and ease his conscience. While he gave away much of his fortune, he did not advocate for fair wages, unions, or worker protections during his time as an industrialist. To many laborers, the libraries he funded were no substitute for better pay or safer working conditions.

Even today, Carnegie’s legacy is debated. His libraries undoubtedly enriched countless lives and played a key role in the spread of public education and literacy. They remain open in many communities and are still used by generations of readers and learners. In Allegheny County, the Carnegie Libraries are alive and well for the citizens to use. Yet, the contrast between how he earned his wealth and how he chose to spend it remains a powerful example of the complexities of American capitalism and philanthropy.

In the end, Andrew Carnegie’s library legacy is both inspiring and troubling — a story of incredible generosity built on a foundation of harsh labor practices. It reminds us that behind every grand gesture, there is often a deeper, more complicated truth.